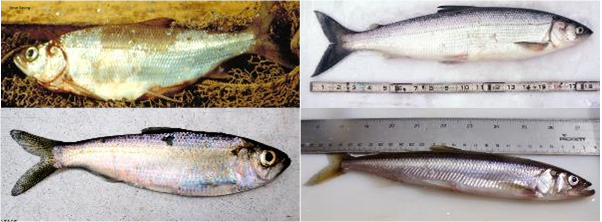

Both species are planktivorous, meaning they consume large quantities of plankton, however, Bighead Carp mainly consume zooplankton and Silver Carp mainly consume phytoplankton which means that they do not compete with one another. Because many of Canada’s native fish species rely on plankton as a food source during development, there is potential for significant competition between the invasive bigheaded carps and the native fishes. In addition, Bighead and Silver carps filter large amounts of plankton out of the water column to a greater degree than native fishes. This has the potential to cause a large decrease in native planktivores, such as Alewife (Alosa pseudoharengus), Bloater (Coregonus hoyi), Cisco (Coregonus artedi), and Rainbow Smelt (Osmerus mordax).

This could result in a decrease of predatory fish species that feed on those forage fish, such as Yellow Perch (Perca flavescens), Lake Trout (Salvelinus namaycush), and Walleye (Sander vitreus).

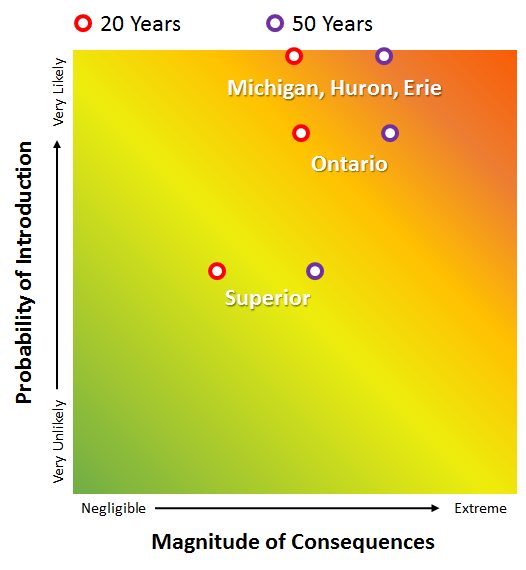

Overall Risk = Probability of Introduction + Magnitude of Ecological Impacts

Probability of Introduction

Table 1 Probability of introduction of bigheaded carps into the Great Lakes by likelihood of arrival, survival, establishment, and spread.

Superior | Michigan | Huron | Erie | Ontario | |

Arrival | Very Unlikely | Very Likely | Low | Low | Low |

Survival | Very Likely | Very Likely | Very Likely | Very Likely | Very Likely |

Establishment | Moderate | Very Likely | Very Likely | Very Likely | Very Likely |

Spread | Very Likely | Very Likely | Very Likely | Very Likely | High |

Arrival

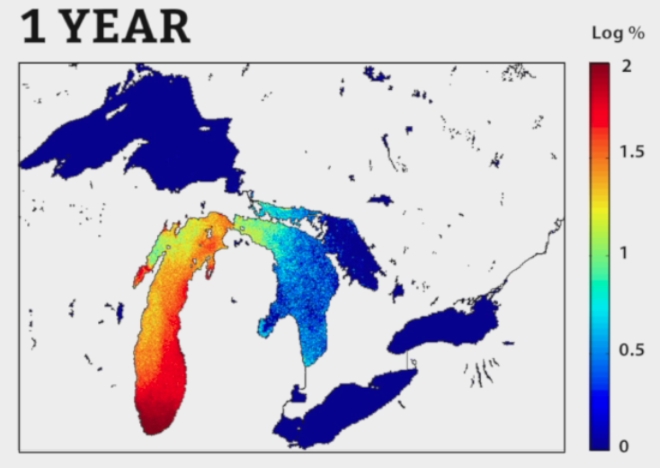

In the Great Lakes, bigheaded carps are most likely to arrive in Lake Michigan. This may occur through pre-existing physical connections such as the Chicago Area Waterway System. However there are other connections of concern through the other Great Lakes including Libby Branch in Minnesota, Eagle Marsh in Indiana, and the Ohio-Erie Canal in Ohio. Arrival caused by commercial trade was also noted as a lower risk pathway but it has much higher uncertainty than the physical connections.

Survival

Determined through habitat matching, bigheaded carps would be able to survive in all the Great Lakes. The environmental conditions of the Great Lakes are suitable for bigheaded carps to survive, and there is more than enough food availability especially in Lake Erie and warmer embayments of the other Great Lakes.

Establishment

There is a greater than 50% chance of successful reproduction if there are 10 mature females and 10 or fewer mature males together, assuming they found suitable spawning rivers. There are at least 49 Canadian Great Lakes tributaries that would provide spawning habitat for bigheaded carps. If they do become established, bigheaded carps could become the majority of aquatic biomass in their invaded range

Spread

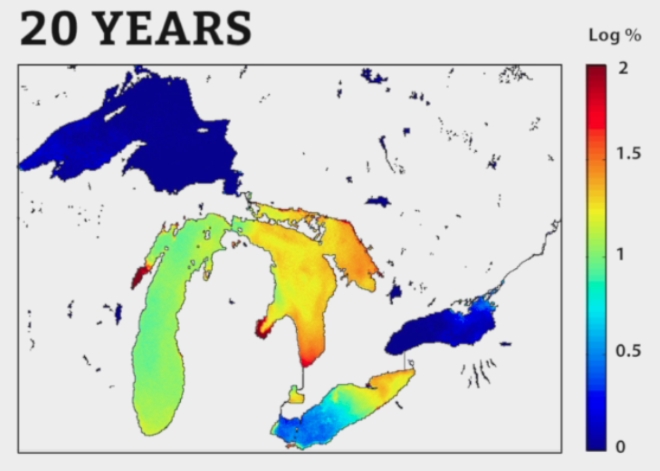

If bigheaded carps were to enter Lake Michigan through the United States, it would take less than 5 years to reach the Canadian waters of Lake Huron. Afterward it would take less than 10 years for them to spread from Lake Michigan to Lake Huron to Lake Erie. Within 20 years it is predicted that there would be large populations in lakes Michigan, Huron, and Erie.

Magnitude of Ecological Impacts

Table 2 Magnitude of the ecological impacts to each lake within a 20-year and a 50-year timeframe.

Superior | Michigan | Huron | Erie | Ontario | |

~20 years | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

~50 years | Moderate | High | High | High | High |

Overall Risk

Should no additional action be taken, the overall risk associated with the potential introduction of bigheaded carps is highest for Lakes Michigan, Huron, and Erie due to proximity of entry point and availability of habitat. The magnitude of consequences increases from 20 years to 50 years as the populations grow.

Binational Ecological Risk Assessment of Bigheaded Carps (Hypohthalmichthys spp.) for the Great Lake Basin conducted in partnership between Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Great Lakes Fishery Commission, and U.S. Geological Survey. The full risk assessment can be found at http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/Csas-sccs/publications/resdocs-docrech/2011/2011_114-eng.pdf